Hello, (InterPlanetary) World

the first post; deep-diving into IPFS, IPLD & IPNS;

A few days ago, when I first decided to create this technical blog, the first post was supposed to be about something entirely different. But also during that time, I decided that I wanted to host it in a decentralized manner, using the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS).

I had worked with IPFS before, used it to host metadata and assets for tokens. Now, hosting a whole blog there, managing CD (continuous deployment) and keeping it synced with my ENS, introduced some challenges which led me to dive deep into how it works… And that’s what I’m talking about today.

Let’s start from the beginning:

What’s IPFS and why would I want to host there?

The IPFS is a protocol that manages a distributed File System.

Essentially, it’s decentralized storage.

And the reason why it’s called InterPlanetary is because it has been envisioned as a protocol fit for data sharing over long distances, and one day, perhaps, even between planets (it’s already running in space with the help of the Filecoin Foundation and Lockheed Martin Space): It doesn’t matter where the data is uploaded from initially, unlike in protocols such as HTTP where the location of the server is what matters. In IPFS, the requested data can be retrieved from the closest available source, and you can be sure of its integrity without communicating with the origin of the contents.

It manages that intergalactic integrity by addressing data based on its contents, called the Content ID (or CID, for short). The CID of a piece of data is derived from that data’s cryptographic hash, so if two users across the Universe upload the exact same file, it will share the same identifier in the network.

Truly decentralized and thus censorship-resistant.

IPFS implementations

In practice, in order to run your own IPFS node, you use one of the available implementations of the protocols. The most widely used one is written in Go and it’s a CLI called Kubo.

Content ID specification

If the CID is derived from the hash of the data, why not use the raw hash digest

directly as the content identifier? IPFS currently uses the SHA2-256 hashing

algorithm, but the protocol has to be future-proof, and in the future SHA2 might

no longer suffice (I’m looking at you, SHA1).

The solution: Self-describing hashes (called multihash), which not only contain the digest, but also which algorithm generated it and its length:

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

Algorithm identifier from the multicodec table (0x12 for SHA2-256) | |

Length of the hash in bytes (0x20 for SHA2-256) | |

| The hash digest |

In order to represent it in a shorter way, base58btc encoding was chosen

(which is just base58, excluding the visually ambiguous characters 0, O, l,

I).

So, while a SHA2-256 multihash would look like this in hexadecimal:

0x12204dfa372740668fc766c6d899a1ccdf1f0752f52331a9d9d657c13247bd599b87The base58btc encoded version would look like this:

QmTb3PouhpDfE4zSRXhW4tBW6z47kbisZ9cNjNPDZ4jazzMuch cleaner, just 46 characters! You’ll notice that, due to the initial fixed

bytes 0x1220, the base58 version always starts with Qm, making the IPFS

CIDs very recognizable.

However, if you’re already familiar with IPFS, you’re probably wondering why

some of your CIDs don’t look anything like that… That’s because what I’ve

explained above is now known as the zeroth version of CIDs, CIDv0.

CIDv1 introduces two new prefixes that improve its self-describing capability:

version and multicodec. The version is obviously to denote the version of

the CID (CIDv2, CIDv3, etc.). The multicodec one denotes the data encoding

method itself (ProtoBuf, JSON, etc.).

So when dealing with binary we now have:

But when dealing with human readable formats there should be a quick way to know which base we’re representing those bytes in…

Introducing yet another table and prefix, the multibase:

A common way to represent CIDv1s is in base32, which looks something like

this:

bafybeicn7i3soqdgr7dwnrwytgq4zxy7a5jpkizrvhm5mv6bgjd32wm3q4Using base32 (prefix b), dag-pb multicodec and being a SHA2-256

multihash, we end up with the very recognizable CIDv1 prefix: bafy.

TIP: If you want to easily analyze your CID, you can use the IPFS CID inspector.

Merkle Directed Acyclic Graphs and IPLD

Enough with CIDs, let’s go back to our network…

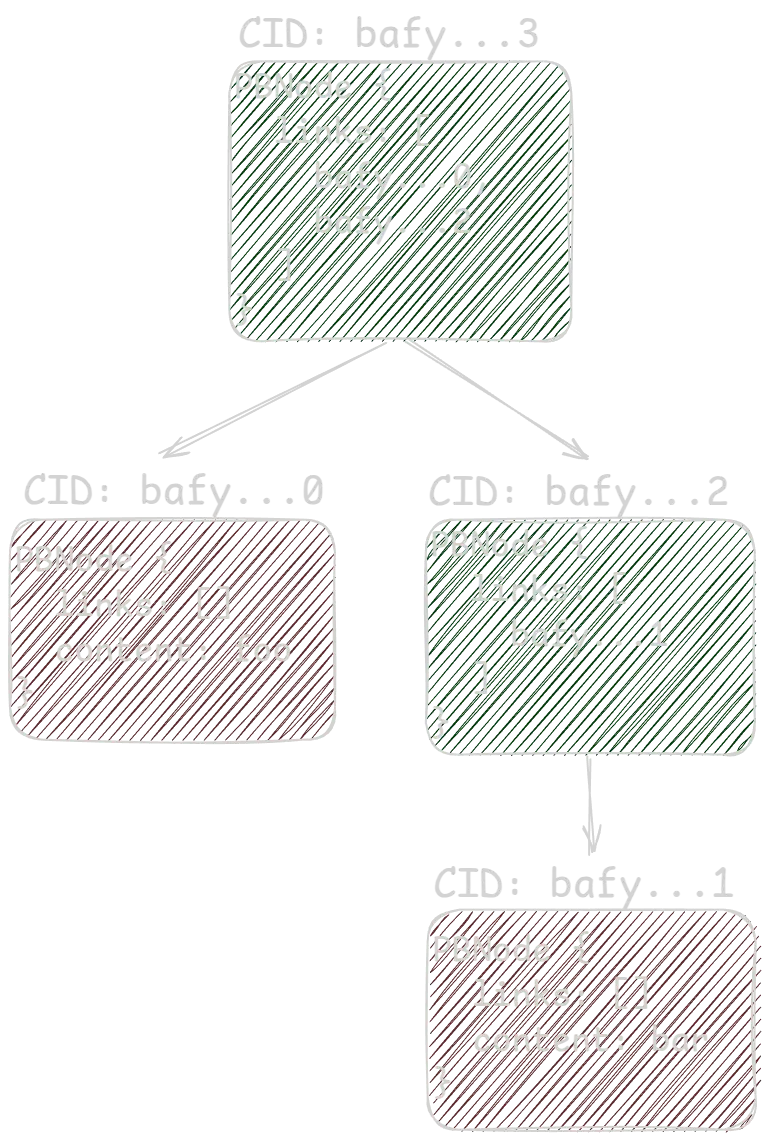

We’re not dealing with simple blobs. It’s a file system, it’s structured and so we need a way to represent and address the hierarchy of files and folders, in a way that any change of contents properly propagate upwards, changing all those hashes/CIDs.

The solution: UnixFS Merkle DAG-PB! UnixFS because it’s a Unix File

System. DAG-PB because it uses that InterPlanetary Linked Data

(IPLD) codec: PB just means ProtoBuf encoding, but what

about the DAG part? The Merkle DAG part…

The file system can be represented as a mathematical graph:

- Each file and folder is a node

- Directed graph: There’s containment in the folders, so there are relationships between the objects (edges) and those relationships have a direction

- Acyclic graph: There are no loops in the graph

Thus it forms a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG). A Merkle DAG, because we are generating the CIDs of the contents of each node, including its data and the CIDs of its child nodes. How cool and efficient is that!?

Here’s the actual ProtoBuf schema used in DAG-PB encoding:

message PBLink {

// binary CID of the target object

optional bytes Hash = 1;

// UTF-8 string name

optional string Name = 2;

// cumulative size of target object

optional uint64 Tsize = 3;

}

message PBNode {

// refs to other objects

repeated PBLink Links = 2;

// opaque user data

optional bytes Data = 1;

}libp2p: Peer IDs and Keys

When in comes to networking, IPFS relies on libp2p, which provides several specs and modules useful for building p2p applications.

In the IPFS network, we need a way to identify not only the content, but also the nodes themselves (also called peers).

Not only identify but also, of course, authenticate. For that the libp2p’s

peer-ids spec is used: Each peer has an associated PeerID derived from a

cryptographic key pair, which is used for authentication.

The keys are encoded in ProtoBuf as follows:

syntax = "proto2";

enum KeyType {

RSA = 0;

Ed25519 = 1;

Secp256k1 = 2;

ECDSA = 3;

}

message PublicKey {

required KeyType Type = 1;

required bytes Data = 2;

}

message PrivateKey {

required KeyType Type = 1;

required bytes Data = 2;

}By default, kubo uses the Ed25519 key type.

To generate the PeerID of a node, its public key is encoded using multihash:

- If the public key bytes length is greater than 42, the key is hashed using the

SHA2-256multihash method - Otherwise, the identity multihash is used (

0x00prefix, as per the multicodec table), which just means that the raw bytes are used directly as the hash

Regarding human-readable formats, they’re treated the same way as the CIDv0

and CIDv1, i.e. They are encoded using base58btc or multibase.

libp2p: Kademlia Distributed Hash Tables

Now that we know how data is being stored and addressed, it’s time to make it available to the network, but how does any node know where it is?

Imagine if a node requested a block and had to traverse the network, node by node, blindly until it found it, how slow that would be… We obviously can’t have a centralized indexer either, and we can’t store the whole global state of which node has which data in each node…

The goal is for each node to contain a manageable amount of information about the data location state. So the state must be equally distributed between all the nodes in the network, and that must ensure reliability and speed (i.e. communicating with the smallest number of nodes) when retrieving content.

It surely sounds like an impossible task, but it has a genius solution: Kademlia Distributed Hash Tables (DHT).

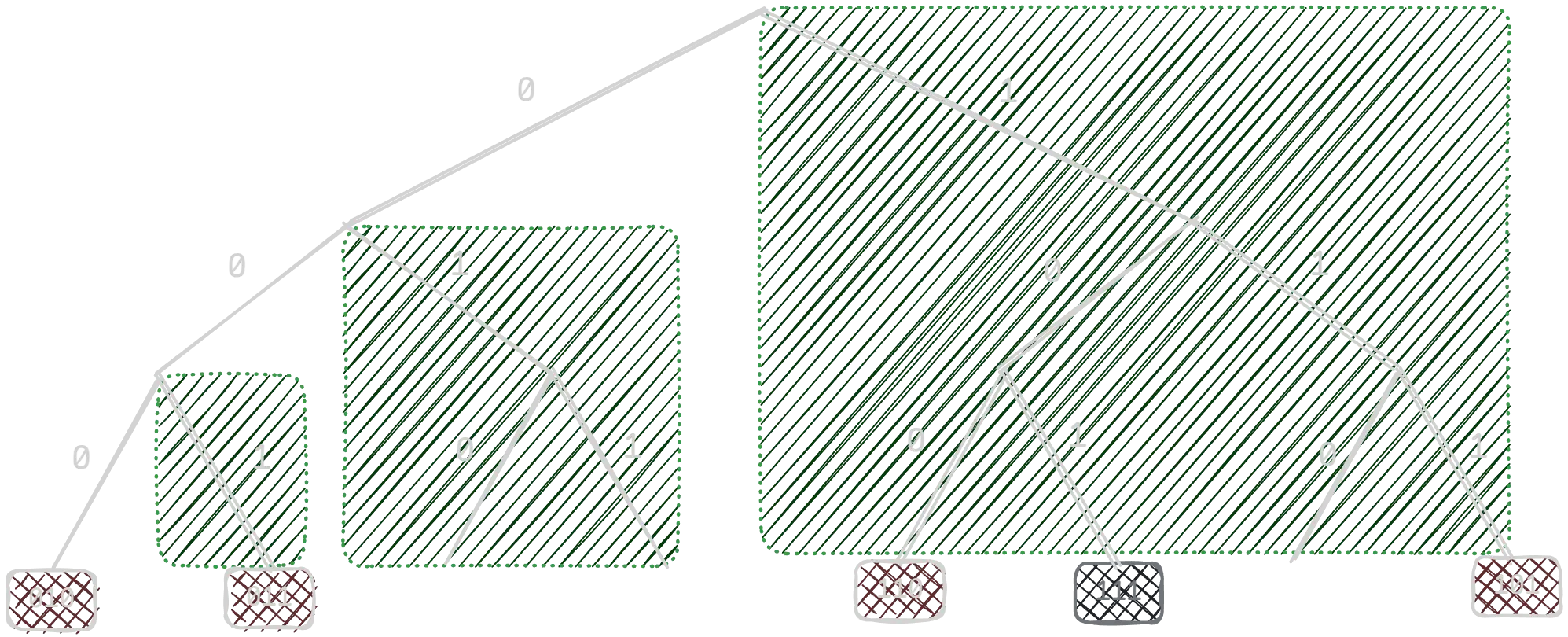

We start by mapping the PeerIDs into 256bit numbers so that we know all peers

fit in a defined finite space, called address space, i.e. mapped between 0

and 2^256-1: To achieve that, we just do SHA2-256(PeerID).

My brain can’t operate with 256bit numbers yet, so in the example bellow, let’s assume our network is super small and can fit it in 3 bit numbers instead.

So we’re peer 010 and the other peers in the network are 011, 101, 110

and 111.

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

-------------------------------

000 001 010 011 100 101 110 111

-------------------------------

O X X X XWe’ll use the bitwise XOR as a way to measure distance between the numbers,

i.e. The distance between 000 from itself, since

We’ll then branch off of the tree from our node at each level, creating groups

(called buckets), and we’ll pick a number

These are called k-buckets, denoted in green in the figure bellow.

The first amazing part is that if each node stores a list like that, then we

can reach any part of the network in just

The second amazing part is that we take advantage of this setup by also

mapping the CID into the address space, SHA2-256(CID), and store the record

that our node can provide that content in the DHT of the closest nodes to that

CID, i.e. The peers where SHA2-256(PeerID) SHA2-256(CID) is the

lowest.

Let’s say our network has 1000000 nodes, we would be able to reach any content from any node in around 20 hops!

IPFS’ DHT uses 256bit address space and

Garbage collection and content pinning

There are only so many nodes in the network, and there’s much more content being uploaded all the time. Nodes store the contents of other nodes, contributing to the availability of those contents, but storage is finite and with time, a node gets filled and must clear old content in order to be able to provide new one (this process is called garbage collection).

A node may choose to prioritize certain content and not garbage collect it over time, pinning it, guaranteeing availability of that content indefinitely.

Services running several nodes can pin your data for a fee, those are called pinning services.

Gateways

A link to an IPFS block looks like this

ipfs://{CID}/{optional-path-to-content}:

ipfs://QmTb3PouhpDfE4zSRXhW4tBW6z47kbisZ9cNjNPDZ4jazz/welcome-to-IPFS.jpgBut most of our browsers don’t support the IPFS protocol (ipfs:// links): For

that, IPFS gateways exist, which are HTTP APIs that interact with a node for

returning resources. All IPFS node implementations provide a gateway.

Example of a gateway URL:

https://ipfs.io/ipfs/QmTb3PouhpDfE4zSRXhW4tBW6z47kbisZ9cNjNPDZ4jazz/

Content immutability and IPNS

One limitation of the network we’ve been describing is that since the data is addressed based on its contents, everything is immutable. If you share a link, it will forever point to the same data. The solution: InterPlanetary Name System (IPNS).

If we want to achieve mutability, the simplest way is by using a pointer between some identifier and a CID, and then we update that pointer with a new CID everytime we want to point to new data.

[fixed ID] -> [CID]And that’s precisely what happens in IPFS: Another record stored in the previously described IPFS DHT is called the IPNS record, which maps the PeerID (or the ID of another key the peer has access to, called name in this context) to an arbitrary identifier (which actually doesn’t have to be a CID, it can also be another IPNS name).

IPNS records are short lived, and since they must be cryptographycally signed there is no pinning in IPNS, the solution is to republish the record periodically.

IPNS records can be accessed through gateways: Just replace ipfs/ with

ipns/.

Hosting on IPFS

Finally, we’ve covered most of the building blocks and features of IPFS, congrats if you have made it this far!

I’ll conclude by outlining some of the challenges I have faced and solutions I came up with in the deployment of this blog in hopes of making the process easier for someone else: Perhaps I’ve already convinced you to host your site on IPFS :).

- For now, I don’t want to run a node 24/7, so I’m using a pinning service (one day I’ll probably get a Raspberry Pi and run it myself, actually), which I call in a GitHub workflow in order to achieve continuous deployment. It automatically commits the new CID to a file in the repository

- Different IPFS gateways have different domains and routes, so all links in

the website must be relative, e.g.

../my-image.webp - I am using my ENS domain (topic for another time) as a decentralized way to

access the blog: Its

contenthashfield supports IPFS, but each on-chain update is a transaction which costs money, and no one wants to pay for gas each time one changes a blog… Fortunately, we have already found how mutability can be achieved in IPFS: We use an IPNS name - IPNS needs to be updated regularly (expires after 24 hours, by default), so I setup a systemd timer that calls a shell script which updates the IPNS record with the latest CID

The link to the source code of this blog can be found in the footer.